by Luwam Habte Abera

1.Introduction

Writing and script style serve as potent identifiers of cultural and national identity. Manuscripts, both ancient and contemporary, convey not only information but also the cultural ethos and socio-political order of the communities that produce them. In this context, palaeography—the study of historical handwriting—extends beyond ancient texts to contemporary narratives, offering a critical lens through which the authenticity and provenance of documents can be examined (Bausi, 2021).

The Ge’ez script—originally a consonantal abjad used in the ancient Aksumite kingdom— gradually evolved into a syllabary through the addition of vowel notations around the 4th century CE, particularly for ecclesiastical and liturgical functions (Ullendorff, 1960). As Ge’ez transitioned into a liturgical language, it gave rise to daughter languages, including Tigrinya, Amharic, and Tigre, each of which adapted the Ge’ez script to meet its phonological needs (Hetzron, 1997; Leslau, 1987).

The Tigrinya alphabet, used for writing the Tigrinya language in Eritrea and the Tigray region of Ethiopia, is a direct descendant of the ancient Ge’ez script (also known as Fidäl/at). This syllabic script is composed of 26 basic consonantal characters, each modified to represent seven vowels, yielding a total of 182 syllabic signs. As one of the oldest alphasyllabic writing systems still in use today, it preserves an essential cultural and linguistic legacy within the Semitic language family of the Horn of Africa.

The earliest known Tigrinya inscription dates to the 13th century and comprises local customary laws inscribed in a Tigrinya dialect, suggesting that the language had begun to be standardised for documentation and public use. The Loggo Sarda customary law is indeed a very important historical document for the Tigrinya language and is a well-known artefact from Eritrea (Kemink, 1991). However, scholarly consensus generally holds that the Loggo Sarda text is a significant early example of Tigrinya, but it is dated to the 15th-16th centuries. The text is found in a manuscript and contains a collection of customary laws, providing valuable insight into the language’s early written form. Both the Loggo Sarda and Wəqro texts are crucial to the history of Tigrinya’s written tradition. The first printed literary work in Tigrinya is Legese Hade Hade, authored by Feseha Giyorgis and published in Rome in 1895.

Unlike Amharic and Tigray Tigrinya, Eritrean Tigrinya has retained the pharyngeal and glottal consonants from Ge’ez (e.g., ኀ [ḫ], ዐ [ʿ], and ሐ [ḥ]), although their pronunciation has often shifted toward more modern, regionally distinctive sounds. It also avoids the duplication of characters that share identical pronunciations.

This article approaches from a philological and paleographic perspective to critically examine a war report published in The Guardian, which includes a disturbing claim of objects and handwritten notes found inside a woman’s womb following acts of sexual violence during the Tigray War, which began on November 3, 2020, and ended on November 3, 2022. The aim is to assess the linguistic and scriptural features of the note to evaluate the reliability and origin of this purported evidence and reflect on the wider implications for media representation in conflict zones.

2. The Obsolescence of Certain Letters in Tigrinya Orthography

In the Tigrinya language of Eritrea, as well as in other languages of the region that use the Ge’ez script, such as Tigre, the letters ኀ (ḫä), ሠ (śä), and ፀ (ṣ́ä) have largely fallen out of common use.

This shift is driven by linguistic evolution, the simplification of the writing system (orthography), and practical usage considerations. The change had sparked debate among scholars and speakers, with one side advocating for retaining these letters to preserve the historical and cultural connection to Ge’ez, the liturgical and classical language of the region, while the other prioritises linguistic simplicity and accessibility for modern users.

The trend of simplifying the Tigrinya orthography has phased out in Eritrea, the use of ኀ, ሠ, and ፀ in favour of their phonetically equivalent counterparts (ሀ(ሐ), ሰ, and ጸ). This practice is evident in educational materials, such as the “First Grade Tigrinya” textbook published in 1973 during the Eritrean armed struggle, which excluded these letters, indicating early discussions on orthographic simplification (Yohannes, 2009).

In Eritrea, post-independence educational books and official documents have standardised the simplified orthography. For instance, government publications and school curricula consistently use ሰ instead of ሠ, ሐ instead of ኀ, and ጸ instead of ፀ. While no explicit government decree formalises this change, its widespread adoption in education and media has made it the de facto standard (Tekle, 2015). This reflects a broader trend in orthographic reform across Semitic languages, where scripts are adapted to align with contemporary pronunciation (Daniels, 1997).

However, opposition to this reform persists, particularly among clergy, traditional scholars, and Ge’ez enthusiasts. These groups argue that the discontinued letters carry historical, cultural, and etymological significance. For example, the Ge’ez script, from which Tigrinya derives, is a cornerstone of Eritrean and Ethiopian cultural heritage, used in religious texts and classical literature. Retaining ኀ, ሠ, and ፀ ensures fidelity to the original forms of words, preserving their etymological roots and connections to Ge’ez (Getatchew Haile, 1996). The 1991 Tigrinya Bible, for instance, retains these letters, as do some scholarly and religious texts, reflecting a commitment to historical continuity.

The primary argument for discontinuing the use of ኀ (ḫä), ሠ (śä), and ፀ (ṣ́ä) in Tigrinya is rooted in phonetics. In modern spoken Tigrinya, these letters no longer represent distinct sounds, as their pronunciations have merged with other letters in the Ge’ez script. According to linguistic studies, such as those by Daniels and Bright (1996), the phonological inventory of Tigrinya has undergone significant reduction over time, leading to the loss of distinctions that once existed in the parent Ge’ez language.

- ኀ (ḫä) vs. ሐ (ḥä): In contemporary Tigrinya, the pharyngeal fricative represented by ኀ is indistinguishable from the sound represented by ሐ. Both are pronounced as a glottal or pharyngeal sound in most dialects, rendering the distinction obsolete (Voigt, 2007).

- ሠ (śä) vs. ሰ (sä): Similarly, the sibilant ሠ, historically a distinct sound in Ge’ez, is no longer differentiated from ሰ in spoken Tigrinya. This convergence is attributed to phonological simplification, a common process in language evolution where redundant distinctions are lost (Ullendorff, 1985).

- ፀ (ṣ́ä) vs. ጸ (ṣä): The emphatic ejective sounds represented by ፀ and ጸ are pronounced identically in most Tigrinya-speaking regions today. Historical linguistic evidence suggests that these sounds were distinct in ancient Ge’ez, but this distinction has faded in modern usage (Lambdin, 1978).

This phonetic convergence supports the linguistic principle of “one sound, one symbol,” which advocates for a streamlined orthography where each phoneme is represented by a single grapheme. Simplifying the script in this way facilitates literacy acquisition, particularly for new learners, and reduces confusion in written communication. As noted by Coulmas (1989), orthographic reforms often prioritise efficiency and accessibility, especially in educational contexts.

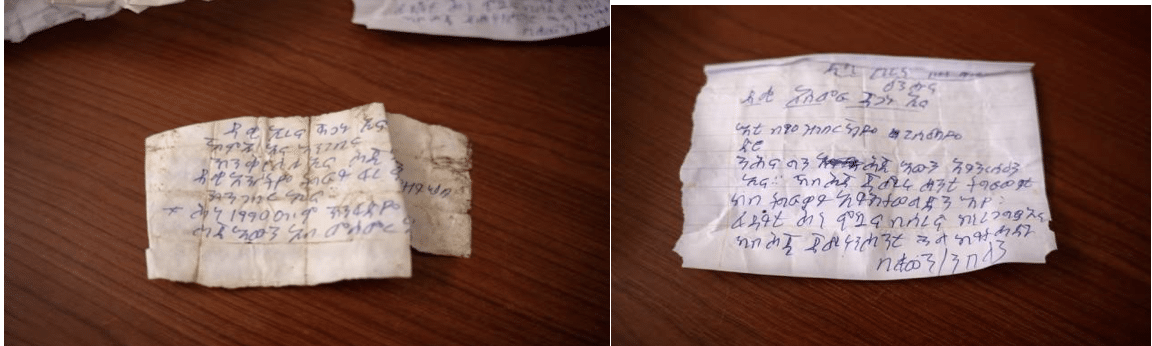

3. The Alleged Manuscript: In the Womb of Tsinat

According to the report, eight rusted screws and parts of a nail clipper, alongside two small notes wrapped in plastic, were allegedly found inside a woman’s womb, remaining there for about two years. The notes carry threatening messages attributed to “the children of Erena” and “the children of Asmara,” invoking revenge for past conflicts and expressing intent to harm Tigrayan women’s reproductive futures.

The first message reads:

- ደቂ ኢረና ጃጋኑ ኢና፡ኸምኡ ኢና እንገብር፡ክንቅፅለሉ ኢና ሕጂ እውን፤ ደቂ አንስትዮ ትግራይ ፍረ ከምዘይህባ ክንገብር ኢና። ሕነ 1990 ዓ.ም ክንፈድዮ ሕጂ እውን አብ መስመር [ኣ…] (“Sons of Eritrea, we are brave,” the note reads. “We have committed ourselves to this, and we will continue doing it. We will make Tigrayan females infertile.”)

- (Children of Erena (Eritrea), we are heroes; that is what we do. We will continue it now as well. We will make it so that the women of Tigray do not bear fruit. We will pay the revenge for 1990 now as well; we are on track.)

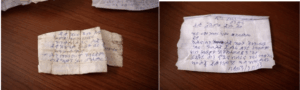

The second message reads:

- […..] ፅንሑና ደቂ አስመራ ጃጋኑ ኢና እቲ ብ 90 ዝገበርኻዮ ረሲዕክዮ ድሮ ንሕና ግን ሕጂ እውን ኣይንርስዕን ኢና። ኻብ ሕጀ ጀሚሩ ሐንቲ ትግራወይቲ ካብ ትግራዋይ አይክትወልድን እየ፡ ፈደይቲ ሕነ ምዃና ብስረና ክነረጋግፆ ኢና። ካብ ሕጂ ጀሚሩ ንሐንቲ ጓል ከይትሓድጉ በልወን/ንበለን(People from Asmara, Eritrea, we are brave. Have you forgotten what you did to us in the 90s? We will never forget. From now on, no Tigrayan will give birth to another Tigrayan. We are ready for revenge. We will not leave any woman behind.”)

- (Wait for us, children of Asmara, we are heroes; you have already forgotten what you did in ’90, but we, even now, will not forget. From now on, a single Tigrayan woman will not give birth from a Tigrayan man. We will prove that we are the repayers of vengeance by our trousers. From now on, do not spare a single girl/woman, do not leave them behind/let’s not leave them behind.)

This manuscript-like note is presented as material evidence of the crimes described

4. Philological and Paleographic Observations

Upon analysing the notes’ language and script, several critical issues arise:

|

Tigrayan Eritrean Usage Usage |

Comment |

|

ኢረናኤረና |

The spelling ‘ኢረና‘ is inconsistent with standard Eritrean Tigrinya spelling for Eritrea. |

|

ኸምኡከምኡ |

‘ኸ‘ is used in Eritrean Tigrinya, and ‘ከ‘ is used in this word. |

|

ክንቅፅለሉ ክንቅጽል (or ክንቅጽለሉ) |

The use of the letter ‘ፅ’ is a primary orthographic inconsistency. |

|

እውንውን |

The use of the full form እውን is more literary, whereas the note’s context suggests a more colloquial ውን would be expected. |

|

አንስትዮኣንስትዮ |

‘አ‘ is not used in this context in Eritrean Tigrinya. |

|

1990 ዓ.ም. ግ 1998 |

The note’s use of the Ge’ez calendar is common in Ethiopia but not in Eritrea, where the Gregorian calendar is the norm for public documents. The year 1990 on the Ge’ez calendar corresponds to 1998 on the Gregorian calendar, a key date in the Eritrean-Ethiopian War. |

|

ፅንሑና ጽንሑና (ጽንሑ) Again, the use of ‘ፅ’ is a major orthographic discrepancy. ክነረጋግፆ ክነረጋግጾ The use of ‘ፆ’ is not standard in Eritrean Tigrinya. አነስተይቲ ኣንስተይቲ ‘አ‘ is not used. ኻብ ካብ The use of ‘ኻ‘ is not standard in Eritrean Tigrinya. ከይትሓድጉ ከይትገድፍወን ‘ሓድጉ‘ is not the typical Tigrinya word for ‘spare’ or ‘show mercy.’ ሐንቲ ሓንቲ The use of ‘ሐ’ is not standard. |

|

Orthographic Anomalies: The writing uses the letter ‘ፀ’ (Tz) in ፅንሑና, commonly found in

Ethiopian script, instead of the Eritrean-preferred ‘ጸ’ (ṣ) in ጽንሑና. Eritrean schools have not used ‘ፀ’ since the 1990s, suggesting the note’s script aligns more with Ethiopian orthography than Eritrean Tigrinya.

Lexical Inconsistencies: The note contains lexical errors uncommon to Eritrean speakers, such as unusual spellings (ደቂ አንስትዮ instead of the typical ደቂ ኣንስትዮ), and inappropriate word choices that contradict local dialects.

Naming Discrepancies: The use of the Ge’ez calendar date (1990, corresponding to the 1998 war) instead of the Gregorian date is significant. While the Eritrean Täwaḥǝdo church uses the Ge’ez calendar, its use in this context suggests a lack of familiarity with common Eritrean historical and linguistic conventions, as it is a standard practice in Ethiopia.

Scriptural Laziness: The overall handwriting style and phrasing appear poorly executed and uncharacteristic of native writers, pointing to a possible fabrication.

The paleographic and philological inconsistencies strongly suggest that the note probably did not originate from its alleged author. Instead, it appears to be part of a staged drama or propaganda, indicating that the author either does not understand how Eritreans write, or it must have been done by Ethiopians themselves if that is proven true.

5. Manuscript Culture and National Identity

The study of script usage reveals that orthography is deeply tied to identity in the Horn of Africa. Eritrea’s post-1990 language policy deliberately differentiated its use of certain letters as an embodiment or reflection of a national identity distinct from Ethiopia. Scripts, therefore, act as cultural markers and forensic tools: deviations in letter forms and vocabulary can signal authorship and authenticity.

This note’s use of Amharic-associated script conventions in a purported Eritrean anti-Tigray message indicates a deliberate or careless crossing of these identity boundaries. It underscores manuscript studies’ relevance to contemporary issues of misinformation and political conflict, where script becomes a symbolic battlefield terrain.

6. Media, Ethics, and the Politics of Believability

Journalistic responsibility requires careful vetting of evidence, especially when reporting on vulnerable populations and sensitive topics like sexual violence in conflict. Visual and textual presentations shape global public opinion and affect post-war justice mechanisms.

The weaponisation of language, script, and imagery can serve political ends, making it imperative to apply interdisciplinary scrutiny—including palaeography and philology—to verify claims. An inaccurate or forged written message not only jeopardises journalistic integrity but can harm the community it purports to defend by undermining genuine victim narratives.

7. Conclusion

The note allegedly found inside a woman’s womb lacks credibility, according to palaeographic and philological analysis. Orthographic and lexical inconsistencies suggest that the message is likely a political fabrication. This case highlights the critical role of manuscript studies in conflict analysis, revealing textual distortions often overlooked in mainstream narratives.

This paper critiques the authenticity of a specific piece of textual evidence allegedly authored by a member of an Eritrean unit. Based on the evidence presented here, the note appears linguistically inconsistent with the cultural and educational background of its supposed authors.

To ensure accurate documentation and responsible representation of conflict victims, researchers, journalists, and human rights advocates must adopt interdisciplinary methodologies. Integrating expertise in manuscript culture into contemporary conflict and media analysis is essential for preserving historical truth and promoting justice.

References

- Allan, S. & Zelizer, B. (2004). Reporting War: Journalism in Wartime. Routledge.

- Bausi, A. (2021). A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea. Brill.

- Bausi, A. et al. (2015). Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies: An Introduction. CMCS Publications.

- Bruck, M. et al. (2009). Grain size in script and teaching: Literacy acquisition in Ge’ez and Latin. Applied Psycholinguistics, 30(3), pp.455–472.

- Chouliaraki, L. (2013). The Ironic Spectator: Solidarity in the Age of PostHumanitarianism. Polity Press.

- Coulmas, F. (1989). The Writing Systems of the World. Blackwell Publishers.

- Daniels, P.T. & Bright, W. (Eds.). (1996). The World’s Writing Systems. Oxford University Press.

- Ephrem Tewolde. (2018). Orthographic Reforms in Eritrea: A Paleographic Assessment.

- Getatchew Haile. (1996). Ethiopic Writing System and Its Historical Development. Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 29(2), pp.1–20.

- Hetzron, R. (1997). The Semitic Languages: An Introduction. Routledge.

- Hofheinz, A. (2010). Script as Identity: The Role of Letter Forms in Arabic Script. Journal of Islamic Manuscripts, 1(1), pp.1-23.

- Kane, T.L. (2000). Tigrinya-English Dictionary. Dunwoody Press.

- Kemink, F. (1991). The Tegrenna Customary Law Codes. In Bahru Zewde et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 11th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, Vol. 2, pp.135– 150. Institute of Ethiopian Studies.

- Lambdin, T.O. (1978). Introduction to Classical Ethiopic (Ge’ez). Harvard Semitic Studies.

- Leslau, W. (1987). Comparative Dictionary of Ge’ez (Classical Ethiopic). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Petros, H. (2010). The Linguistic Relationship Between Ge’ez, Tigrinya, and Amharic. Journal of Afroasiatic Studies, 12(2).

- Raz, S. (1983). Tigre Grammar and Texts. Undena Publications.

- Schiffrin, D. (1987). Discourse Markers. Cambridge University Press.

- Shack, W.A. & Getatchew Haile. (1999). A History of Tigrinya Literature in Eritrea: The Oral and the Written, 1890-1991. Africa World Press.

- Tekle, M. (2015). Language Policy and Orthographic Reform in Eritrea. Eritrean Studies Review, 6(1), pp.45–67.

- Tesfai, T. (2012). Tigrinya-English Advanced Lexicographic Dictionary. Hdri Publishers.

- Ullendorff, E. (1960). The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People. Oxford University Press.

- Ullendorff, E. (1985). The Semitic Languages of Ethiopia and Their Contribution to General Semitic Studies. School of Oriental and African Studies, 48(2), pp.259–272.

- Voigt, R. (2007). The Phonology of Tigrinya. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics, 28(2), pp.123–145.

- Woldemikael, T.M. (2003). Language, Education, and Public Policy in Eritrea. African Studies Review, 46(1).

- Woldu, H. (2020). Orthography and Identity in the Horn of Africa. University of Asmara Journal.

- Yohannes, T. (2009). Educational Reforms in Tigray: A Historical Perspective. Tigray Educational Journal, 12(1), pp.33–50.

(Associated Medias) – Tutti i diritti sono riservati

L’articolo Handwriting in the Wound: A Philological and Paleographic Critique of a War Narrative in The Guardian proviene da Associated Medias.